Revolution From My Bed: No One Should Die For Fashion

Image Source: Asad Mohammad / ABACA/PA Images

This is a guest blog post by Mary Beth Graham, events and policy advisor at the Scottish Women’s Convention, and my fellow volunteer at Fashion Revolution Scotland.

“Fashion is at its best when it’s working disruptively.”

– Dilys Williams, Founder and Director of Centre for Sustainable Fashion.

I love the root of fashion; its ability to manifest self-expression and social identity, and the complexity of trends and design. We know that fashion, clothing, textiles, shopping and style mean different things to different people. Each one of us has a unique thought process and purpose to our selection of items that we choose to wear each day. What (almost) all of us have in common is that we clothe ourselves. And what each of these pieces have in common is that someone, or indeed a chain of individuals, made them.

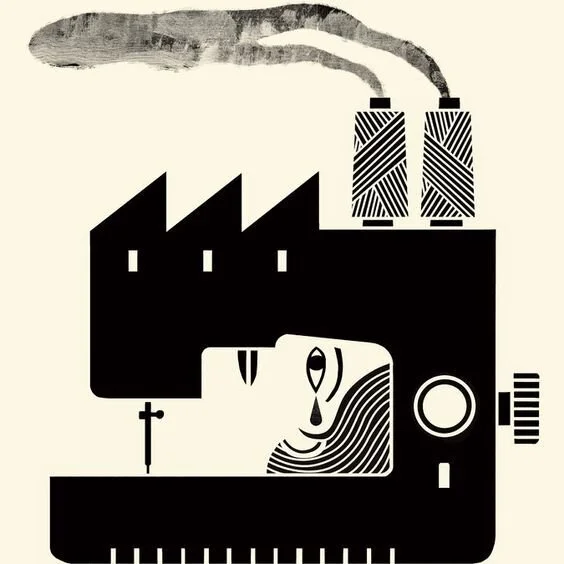

It’s because of this evident truth that I feel Fashion Revolution’s message should reach everyone. It’s our human responsibility to consider Who Made My Clothes – not just ‘fashion lovers,’ not just those ‘in the industry,’ not just the ‘ethical bloggers,’ and not just ‘women’, but every individual who has ever purchased and worn an item of clothing. Why? Because the global clothing and textiles industry, as it stands now, is entrenched in abuse, exploitation, injustice and destruction. This needs disrupted.

Image Source: Munir Uz Zaman / AFP / Getty Images

Which leads us here – to Fashion Revolution Week 2020, amidst a global pandemic, the most challenging and uncertain time many of us will ever live through. In a time of unified isolation, I’m inviting you all to join me in a Revolution From My Bed. This blog series will uncover the plethora of human rights violations that have quietly come to define the global clothing and textiles supply chain, untangling the complex relationship between business, law, policy, gender and culture. I hope it will equip you with the knowledge to rise up, and with conviction, demand that the people who make our clothes are visible and their human rights are respected.

The power and magnitude of fast fashion is born out of the weakness and diminishment of International Human Rights Law.

The term ‘Fast Fashion’ is defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as “clothes that are made and sold cheaply, so that people can buy new clothes often.” We’ll return to this definition later, but to elaborate on the colossal scale this industry, let’s quickly look at some of the facts available.

The clothing and textile industry, as a whole, contributes $2.4 trillion to global manufacturing, and employs around 75 million people worldwide. In the last 15 years, clothing production has approximately doubled and around 150 billion garments are now produced annually. Long gone are the days of two collections per year; Zara claim to put out 24 with H&M releasing between 12 and 16. In fact, during The True Cost, we hear Lucy Siegle (journalist, author, and one of my personal heroes) discuss how these fast fashion chains now arguably release 52 collections per year, with new garments entering stores every single week.

As a brief case study, let’s look at Zara closer. A Spanish brand of humble beginnings, their first store opened in 1975 in the city of A Coruña, and within ten years they incorporated their handful of stores under Inditex. Fast forward to 2020, and they have nearly 3,000 stores in 96 countries, thanks to their “ability to develop a new product and get it to stores within two weeks, while other retailers take six months". I don’t need to tell you that this model of retailing has created a colossal income for the company. In the financial year 2018-2019, they were ranked as the leading European based fast-fashion company, making just over 22 Billion GBP. Out of curiosity, I’ve worked out this would equate to somewhere around 1,409,881,176 of these tops or 751,717,239 pairs of these “premium” jeans.

Maybe a clearer way to illustrate their magnitude is to tell you that Amancio Ortega, founder of Inditex (of which he now owns around 60%), is worth 64.1 Billion USD (around 52 Billion GBP) Back to Who Made My Clothes - I think at this point it is imperative to reflect on the disparity of wealth between the maker and the profiteer. The legal minimum wage for garment workers in Bangladesh is 8,000 taka (£73.85) a month. If this minimum is respected (again, we’ll come to this later), it would take one of these workers around 58,677,499 years to earn this amount of money.

Dizzying. Or actually, more honestly, despicable.

Image Source: Clean Clothes Campaign

We’re so often told by fashion companies that their power is our fault. The consumer wants more! This country adores fashion! These ladies just love to shop! The Kardashians made us do it! Instagram!

And yes, undoubtedly, there’s elements of truth within each of these claims. But what we need to do is take a step back and look beyond this tired and evasive excuse of meeting demand with supply. We should recognise the space in which consumer’s expectations and demands grew through the increasing provision of these on-trend goods at lightning speed for incredibly low costs. This has not always been the shape of this industry. It’s important we remember that and look closer at the structures that have enabled this drastic change. It’s also important to note because it shows this industry is able to fundamentally change.

We’re also told by fashion companies that their power is in fact a force for good. They bring capital, jobs and technology, and in turn they promote numerous human rights, such as those to work, housing and adequate living standards, education, health, and more. Again, there are elements of truth here. But the wider reality is grim. Human Rights Watch describe the plethora of human rights violations in the global industry –

Image source: Mitch Blunt

According to Human Rights Watch, “In countries around the world, factory owners and managers often fire pregnant workers or deny maternity leave; retaliate against workers who join or form unions; force workers to do overtime work or risk losing their job; and turn a blind eye when male managers or workers sexually harass female workers.”

The people who make our clothes are exactly that – people. For brands, economists, policy makers, anyone, to defend the exploitations rife throughout this industry with the blind excuse of providing jobs, is disturbing.

Or again, more honestly, despicable.

Finally, the loudest and most common claim by fashion companies? It is simply not their responsibility. The goods are outsourced, of course. The supply chain is impossible to supervise. The producing country should be sorting these problems. They set the wages. They enforce regulations. “They should have done better.”

And this is where I find myself defeated. Defeated because of its devastating truth. We have created a multi-trillion-dollar global industry within which those at the top, feasting on wealth, are not accountable to those at the bottom, vulnerable and oppressed. The interconnected, global nature of the fashion industry, and indeed most aspects of present-day business, has brought one our greatest and most complex challenges in the modern world;

How do we consistently protect and respect Human Rights across every jurisdiction and in every community that a Corporation, and in fact an entire industry, touches?

I hope you’ll join me in the next stage of the Revolution From My Bed, where we will uncover the fashion industry’s place within International Human Rights Law, looking at the power structure within which this fundamental responsibility and accountability is lost.

Until then, take care, and remember to ask your favourite brands, #WhoMadeMyClothes?

Image Source: Fashion Revolution