Inherent Dignity? Not In This Industry.

This is a guest blog post by Mary Beth Graham, events and policy advisor at the Scottish Women’s Convention, and my fellow volunteer at Fashion Revolution Scotland.

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” - Article 1, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

We left the first part of Revolution From My Bed discussing the concept of accountability. In my opinion, responsibility and accountability are key to justice. They are vital tools to ensure that all human beings are treated equal in dignity and rights. As much as a dreamy optimistic view on human nature is tugging me away from this point, the sombre reality is that if there is no-one, or nothing, to hold accountable for violations and exploitations, dark and dangerous places appear. Places like much of the fashion industry. Places like Rana Plaza seven years ago. Places where global powers have vanquished human dignity.

The next step of this series will weave in and out of fashion. We’ll look at the shape of global business now, as it has evolved, and then look back in history, to the establishment of International Human Rights Law. As we go through the progression of both, we’ll begin to understand why protecting people from power in our industry has become an incredibly complicated task.

Image Source: Money Fashion Power Fanzine, Fashion Revolution.

Globalisation defines the complexly intertwined world we live in today and has emerged because of fundamental changes over the last fifty years, like advances in technology, reduction of political and economic barriers, and free movement of capital. The biggest winner has been Business, with the authority and influence held by Transnational Corporations creating an ongoing significant challenge, particularly in law and policy relating to their impacts on individuals and communities. (‘Transnational Corporation’ / ‘TNC’ is the term for a company that operates its business in several countries. They’ll usually go to these places for “cheap raw materials, cheap labour supply, good transport, access to markets where the goods are sold and friendly government policies.” Sounds familiar, right?)

These businesses are now central to most global movements of investment, technology and trade, which has, in turn, given them immense strength within politics. As we discussed in Part One of this series, the international expansion of supply chains has seen fashion companies considered as a force for good in many countries, bringing capital, jobs and technology, and in turn promoting numerous human rights. However, with this widespread level of influence and profitable activity, comes the inescapable reality of negative social impacts too, particularly concerning the protection of human rights. In turn, the responsibility and accountability held by these multinational corporations has become a highly concerning issue.

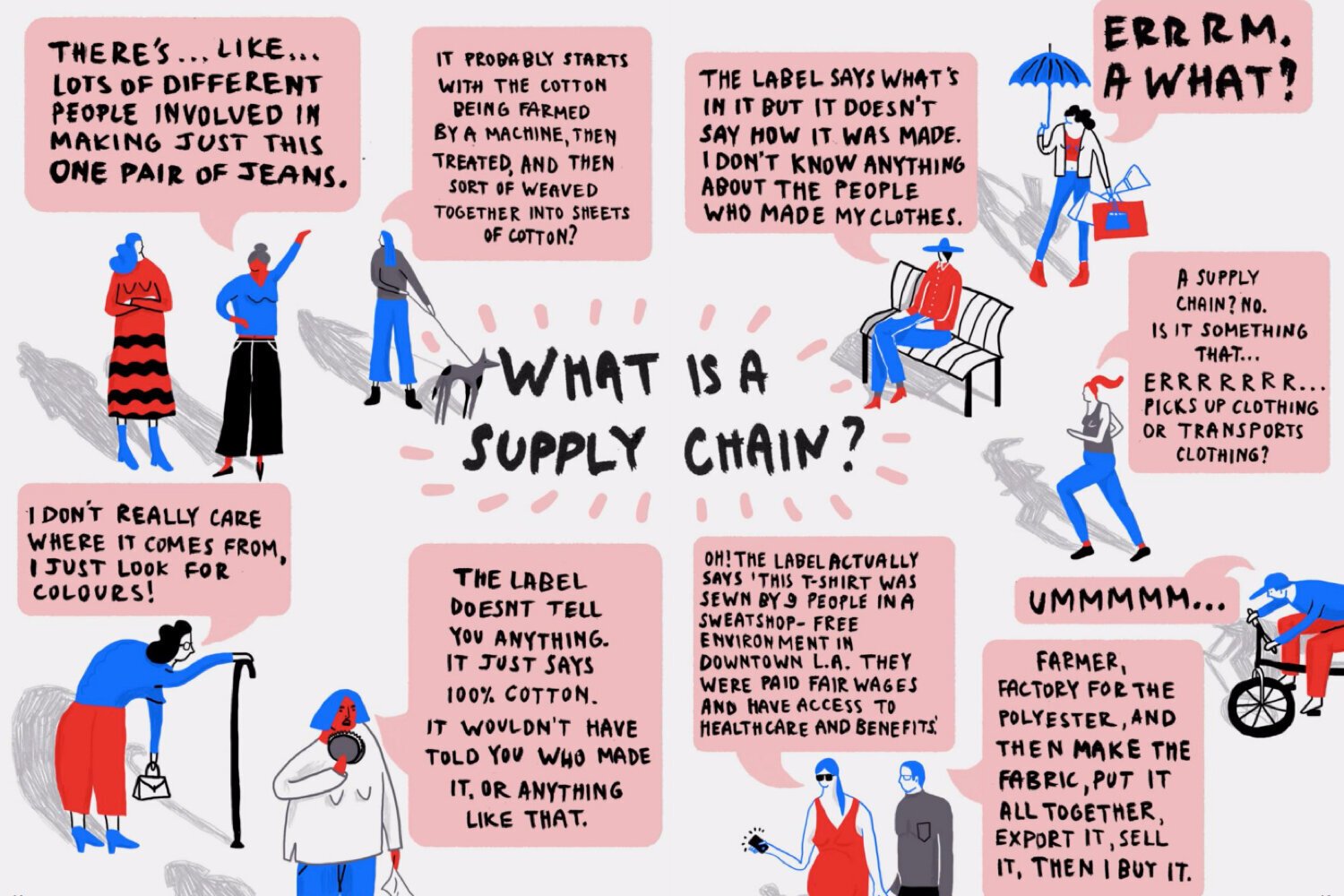

Image Source: Josephine Rais

With a supply chain that spans throughout countless countries and communities, from the sourcing of raw materials and fibres and the spinning, weaving, dyeing and finishing of textiles, to the manufacturing of garments and finally distribution to both suppliers and then consumers, the process of fashion involves millions of people around the world. The incredibly extensive nature of the industry has become a powerful illustrative example of Globalisation. Fashion, a product and practice once derived from our pursuit of functionality, creativity and social expression, has become synonymous with human rights violations on a worldwide scale.

Certainly, garment manufacturing has not taken a sudden, dramatic downfall, as one journalist states, “The menial workforce has always been susceptible to exploitation, and for nearly a century, the garment industry’s sweatshops have acted as de facto laboratories for a variety of abuses and endangerment.” However, the elements of Globalisation - easier trade, advances in technology, reduced transport costs - have collectively enabled labour-intensive industries, such as garment manufacturing, to access low-cost labour markets, typically found in Developing Countries. We have seen this lead to the internationalisation of fashion supply chains at an astonishing speed, for which many Developing Countries cannot, have not, or choose not to, prepare for in terms of their own human rights governance and protection.

At this stage, we understand the changes that have happened which have allowed businesses and their supply chains to go global. Now, we need to come back to #WhoMadeMyClothes. Transnational Corporations are commonly found to undermine human rights in four broad ways. First, and arguably the most recurring across many developing countries, is the driving down of employment standards and labour protection measures. Considering the increasing ability to outsource parts of supply chains to areas with lower work standards, businesses are known to use strategy and tactics to exploit a ‘more profitable’ workforce. Second, corporations can purposefully move into corrupt or undemocratic countries to undermine local workers’ rights, and have been accused of collusion with these regimes, some of which systematically imprison, torture and kill opposition groups, including trade unionists. Third, corporations have taken unethical, unsafe routes to profitability in countries with weaker or flawed regulations, through actions such as bribery or detrimental obstruction of local community’s health necessities. Finally, many international businesses are accused of practices that cause environmental damage, impacting local and indigenous communities land, food and water.

Sadly, we watch fast fashion brands tick each of these boxes almost constantly. How is this fair? How does it continue? And, how is it legal? This is the really important point. There is, astoundingly, no international regime of human rights law governing the transnational activities of corporations. And thus, corporations continue to exploit, damage and harm, violating the universal and inalienable rights inherent to all, while avoiding direct legal accountability and responsibility.

So who can we, as fashion consumers, fashion revolutionaries, hold accountable for ensuring human rights are respected and realised in an industry we care so much about? Who do we demand makes things better for the people who make our clothes? This is made complicated because of the significant global changes in power dynamics since international human rights were first developed. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted by the United Nations in 1948, was the first internationally recognised document to manifest the concept of inherent, equal and inalienable rights for all humankind, and posed these “as the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.” It’s really important here to note that this was not technically a legal document, but instead a ‘declaration of intent’ that brought together countries around the world with a clear purpose and goal. If you want to find out more about these, watch here – or you can head to our Fashion Revolution Scotland Twitter, where I presented the UDHR in its entirety for Fashion Revolution Week 2020.

The development of core international human rights law instruments (i.e. written documents that would become sources of law relating to protecting human rights) soon followed. These developed and translated the UDHR into practical, descriptive and, vitally, legal rights, and so at this point, the concept of appointing responsibility became apparent. It was decided that each country would hold an obligation to promote and enforce these rights, which they would then be expected to do through their own domestic law. While these were an incredible step forward in the global realisation of basic rights and freedoms, the gravity of assigning sole responsibility to the state alone would prove contentious over time, and ultimately lead to weakening their capabilities and effectiveness in our contemporary, globalised, commercially-focused world.

As we previously discussed, Globalisation has seen countries continuously handing over more power and authority to private institutions. As a result, there is now an increasingly widespread understanding or acceptance that states alone can no longer adequately guarantee respect for and realisation of human rights. This significant change in the power dynamics and priority interests of states has undoubtedly led to the denial of responsibility and neglect of human rights accountability, particularly in relation to rights that pertain to labour and the environment. Every time a country’s government turns a blind eye to child labour, to pay below minimum wage, to the beatings of trade unionists, the sexual abuse, the fractured walls on buildings. Every time, it shows the growing power of fashion brands and the weakening of states. The reliance on practice and enforcement within a country’s own, domestic law to uphold international law has opened an increasingly complex space, referred to as the ‘Governance Gap’ , within which we see businesses reject legal accountability for their actions impacting upon human rights, on the premise that it is the state’s responsibility to enforce rules.

So what happens when these Corporations, global fast fashion brands, hold no human rights obligations in a legal sense? Dark and dangerous places appear. In the next part of Revolution From My Bed, we will look closer at the different ways human rights are impacted within fashion, in the particular context of the Bangladeshi Ready Made Garment Industry.

Until then, take care, and please take a moment to remember the 1,138 people who were lost in Rana Plaza, on the 24th of April 2013. May we continue to equip ourselves with the strength, knowledge and compassion that is needed to transform this industry.

Image Source: Getty Images